There are thousands of gadgets for electronic music creation. Sometimes it even becomes hard to keep on track with all those new inventions. However, there is no gadget that could compare to the real connection of two musicians playing together. Or is there? Noise Orchestra, a group of sound artists from the UK, created ANU (Autonomous Noise Unit), a device meant to support musicians to play music together online. So without further ado, we invite you to learn more about ANU and Noise Orchestra through this short interview with the masterminds behind them – David Birchall and Sam Andreae.

Would you please tell us about the beginning of the Noise Orchestra? Why did you decide to work together, and when did it happen?

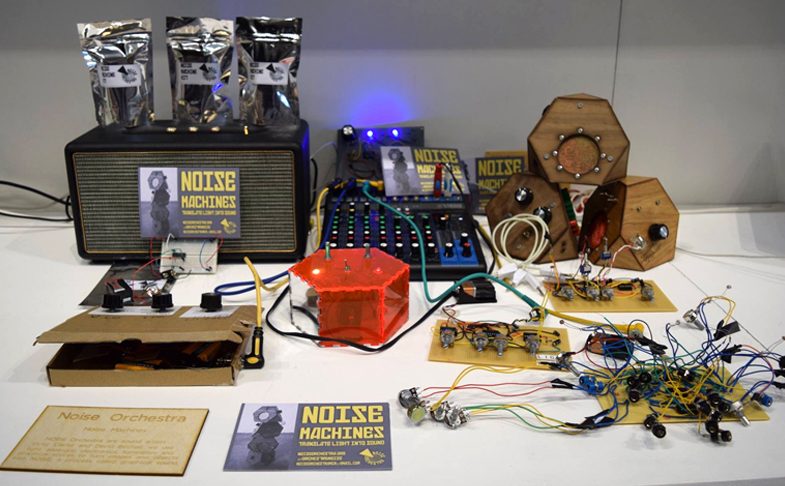

David Birchall: Myself and Vicky Clarke both became interested in making DIY electronics at about the same time in 2014. We were trying out Arduino projects, things from Nick Collins’ amazing electronic hardware hacking projects book, making things based on Byron Gysin’s dream machines with turntables, having lots of fun. Then in 2015, our second project together was this big 3-month residency at the National Media Museum in Bradford, where we were working building circuits and designing visuals to play the light-sensitive circuits based on their archive nearly everyday. This kind of launched us into being busy most of the time with projects with museums, galleries, and DIY makers for quite a few years. At the same time, in 2014, I was also working with Sam Andreae, who came on board as part of the ANU project and a residency at The Penthouse in Manchester. Again, here we were exploring homemade circuits with Nick Collins, making long string instruments and free improvisation. The result of that residency was a huge installation featuring a long string instrument that went up two sets of stairs 4 storeys high and down a long corridor, a homemade PA system with empty beer cans as speakers, a mobile phone rhythm machine, and different improvised performances, it was quite something!

Is there a story behind your name Noise Orchestra? What does it mean to you?

David Birchall: So the way me and Vicky knew each other in the first place was by working together on community arts projects with kids in schools in Manchester. So we had a project we were working on together with some kids making instruments from trash, recycled objects, anything we could find, and making scores with the kids to play the instruments. This was at the same time as we were getting very interested in DIY electronics and we had come across Andrei Smirnov’s book “Sound in Z”, which describes the many different approaches taken to reinventing music and music production methods in the 1920s after the Russian revolution. One of the trends described in the book is the emergence of ‘Noise Orchestra’s’ during this period which explored how everyday sounds could be organised as music; Arseny Avaraamov’s city wide works are the best-known examples of this. A parallel development in Noise Orchestra’s in Russia in the 20s led to a movement of DIY acoustic instrument builders which were used in theatre sound effects, and we saw a parallel with this and the project we were doing with the kids, so we decided to use the name for that project! I think we also see this idea of the freedom and openness of possibilities for those working with music offered to people in that brief period of Russian history as being really resonant to us. As part of the residency at The Media Museum, we also were able to visit Moscow for a week to meet and talk with Andrei about some of the ideas and machines we were interested in from the book, which was great.

We have noticed that you express yourself through a few different art forms. Why so? Please share your favourite/most important projects with us!

David Birchall: A big part of Noise Orchestra is that often the projects will be about our learning in public as part of the project with collaborators with special technical knowledge as well as the general public taking part in some way and learning as we learn. I think for me, as an improviser, taking this exploratory, improvised approach to circuits is an important part of the process. I think one of my favourite projects was the Swarm project, where we collaborated with a number of different designers in the UK and Italy to make bespoke portable noise-making machines that we used to make soundwalks at night time with the public in the UK and Rome. The immense collaboration we have just done with developing the first iteration of the ANU has also been really important. It stretched our knowledge of circuit design, building, music-making and gave us the chance to work with totally different people, Sam Andreae, Tom Ward, who had a coding background and then tested the hardware globally with improvisers and musicians. Who it was great to connect with! The way this project was funded through Innovate UK was also new for us in that it brought us back to thinking about how the project could be developed through an innovation and technology framework rather than the art lense we often apply.

Please tell us more about ANU. What are its main functions, and why should electronic music creators try it out?

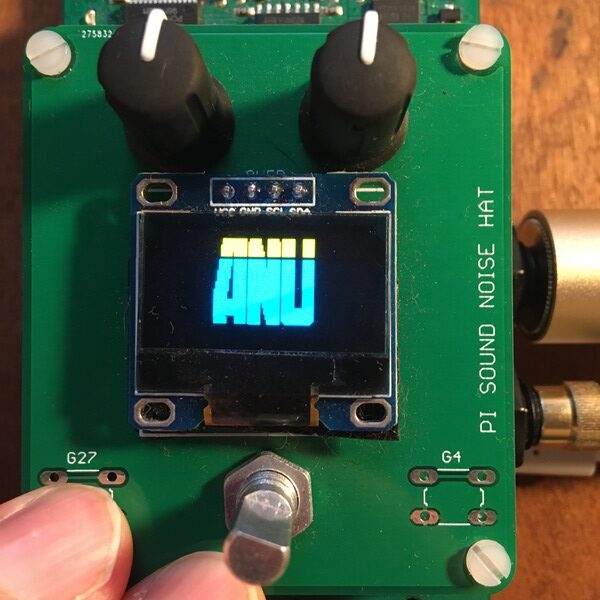

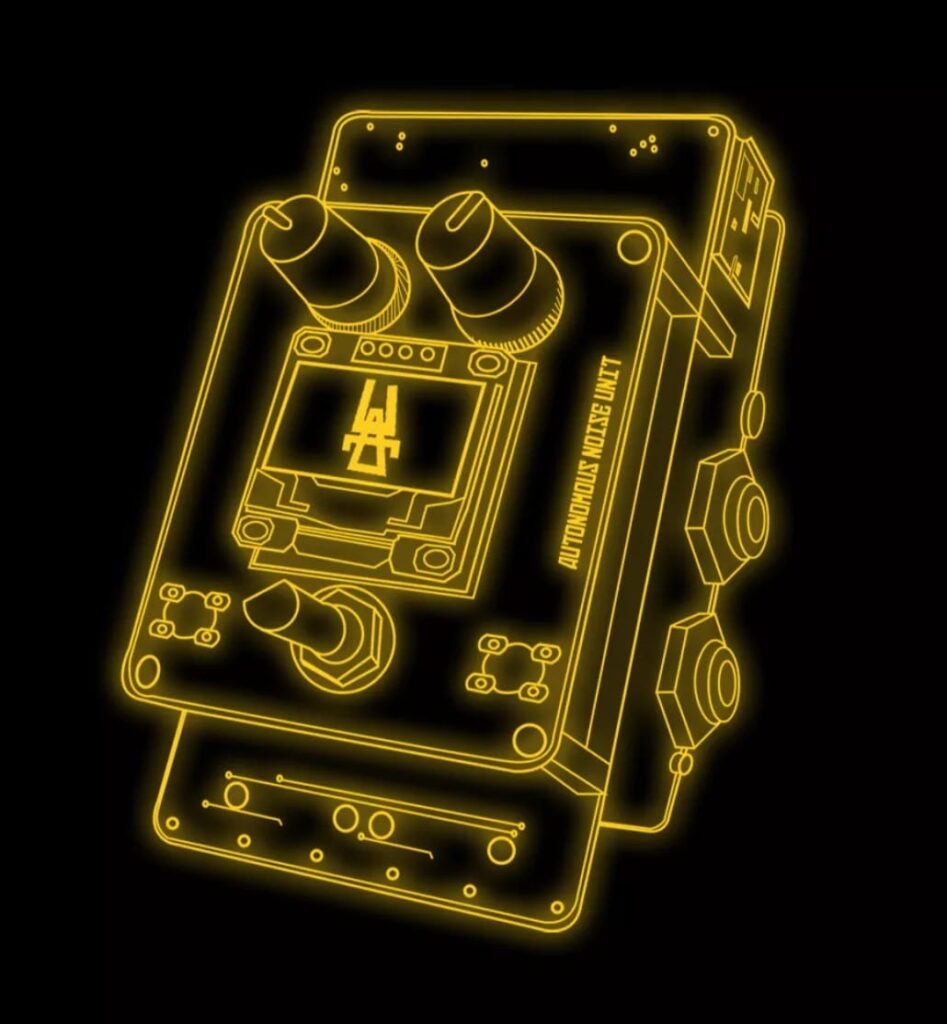

David Birchall: ANU stands for Autonomous Noise Unit. It is a stand-alone unit that combines a Raspberry Pi running JackTrip software with a soundcard and a bespoke pi-hat made and designed at Noise Orchestra HQ. There are two iterations of ANU, one with the Pisound! The ANU allows a user to plug in their instrument and headphones and then, at the push of the switch, connect directly to their colleagues in different parts of the world in a private server to allow them to play music together with really good audio quality. We realised at the start of the pandemic that JackTrip offered the best possibility for audio quality when playing remotely but was not so user-friendly. As a result, we tried to make a device that was as simple as possible so musicians could spend more time playing together and less time on the technical considerations; and so ANU was born!

Sam Andreae: The ANU grew out of our own experiences adapting to remote music-making during the pandemic. Early on, we explored many methods (roaming mobile phone jams, synchronous but remotely inaudible music, lo-fi Jitsi sessions), which all drew out different and intriguing results. We started to explore JackTrip for the promise of high-quality, low-latency experiences. The first time we connected, I was amazed at how it felt to speak and hear with such clarity over a network. The ANU is our attempt to make this experience more accessible and less tied to a computer/studio environment. I think part of the reason for this was to keep the music-making experience fun. Most of the sessions we’ve organised have been with familiar collaborators from the broad world of improvised/noise music. We make spontaneous music together, which is unpredictable and joyous. Retaining this in a remote setting is a challenge. The high audio quality was really important because then the listening could be meaningful, then also keeping the experience as immediate and direct as possible (not getting bogged down in too many technical details). The only thing you can’t skip is a good soundcheck!

On the technical side, JackTrip is a network music-making protocol. It’s been used for many years in networked music circles, and as a result of the pandemic and national lockdowns, there was interest coming from many new areas. Development has been rapid over the last years, as well as some organisational changes around the project. There are loads of interesting developments, including other autonomous devices like ours.

When connecting to remote peers using JackTrip, there are two different connection options. One being peer-to-peer, which requires some port opening on your local router, and the other being via a hub server. The latter makes connecting simpler and can also support more connections (musicians) per session. Although the ANU supports both methods, we focused on the hub server method and built our own custom server code with added features, including panning, icecast stream broadcast, and recording. So with your ANU, you can type in the peer or server address using the interface, connect your mic and headphones, press connect, and off you go.

Code for both the ANU and custom server can be viewed here:

ANU: https://github.com/noiseorchestra/autonomous-noise-unit

Custom server: https://github.com/noiseorchestra/jacktrip_pypatcher

Why was it important to include Pisound in ANU? What do you like about Pisound the most?

David Birchall: We needed a high-quality sound card as part of the ANU! What was great about Pisound was that when we tested a bunch of sound cards, the latency within the Pisound came back as super low, so ideal for our purposes. Having the onboard input and output amplifier and controls on the Pisound is a big plus for us as that basically saved us having to design that aspect into our Pi HAT. Again, the really well-designed 14 pins in and out of the pisound meant it was easy for us to integrate the Pisound functions with our Pi HAT design which added an OLED screen and rotary switch so users could easily scroll through to connect and change functionalities in Jack Trip.

Not only do you create art, but you also share your experience with others. Why do you think it is important to educate people on electronics and circuit building, improvisation, and graphical sound?

David Birchall: I think our experience of the Noise Orchestra project growing out of our previous work in education and really the function of the projects we do actually being about how our learning and collaboration with others develops into an artwork or experience makes us really keen to share what we know and have learnt. We think it’s important to empower people and reveal what we know and the ways we use it.

Do you have any exciting future projects coming our way? Please share them with us!

David Birchall: We are currently working on a follow-up project to the initial ANU development: ANU Festival of Improvised Music! It will feature live globally networked remote performances from David Birchall (Manchester), Tyler Damon (Chicago), Sasha Elina (Moscow), Odie Ji Ghast (Newcastle), Dirar Kalash (Ramallah), Aziz Lewandowski (Berlin), Ikbal Lubys (Yogyakarta), Yan Jun (Beijing) Maggie Nicols (Carmarthenshire), Kae San (Tokyo), Fritz Welch (Glasgow) 3-5 pm GMT on the Saturday 4th and Sunday 5th of December. This is a great follow-up as these amazing experimental, and improvising musicians helped us test and develop the hardware in the first phase.

Follow Noise Orchestra

Official ANU WebsiteOfficial Noise Orchestra Website

SoundCloud

Twitter: Noise Orchestra

Twitter: David Birchall

Twitter: Sam Andreae

Twitter: Vicky Clarke